https://x.com/sekarreporter1/status/1729821196340871285?t=g11WS68caEwDw6CWv5gXqg&s=08 In the upshot, (i) All the writ appeals viz., WA.Nos.682 to 687 of 2023 are dismissed and the directions issued in the writ petitions are directed to be complied with by the appellant authorities. The rules of reservation as set out by the Apex Court in the Judgments mentioned in paragraph no.25 of this judgment, are to be scrupulously followed. (ii)The Writ Petition in WP.No.7412 of 2013 is disposed of, with the direction as stated in para 22 of this judgment. Consequently, all the miscellaneous petitions are closed. There will be no order as to costs. [R.M.D,J.] [M.S.Q, J.] 20.11.2023 r n s Index: Yes / No. Speaking order/ Non-speaking order Neutral Citation: Yes / No. R. MAHADEVAN, J. and MOHAMMED SHAFFIQ, J. r n s To 1.The Secretary, The Tamil Nadu Public Service Commission, TNPSC Road, V.O.C. Nagar, Chennai – 600 003. 2.The Controller of Examinations, Tamil Nadu Public Service Commission, TNPSC Road, V.O.C.Nagar, Park Town, Chennai – 600 003. W.A.Nos.682 to 687 of 2023 & W.P.No.7412 of 2023 & other connected miscellaneous

IN THE HIGH COURT OF JUDICATURE AT MADRAS DATED : 20.11.2023

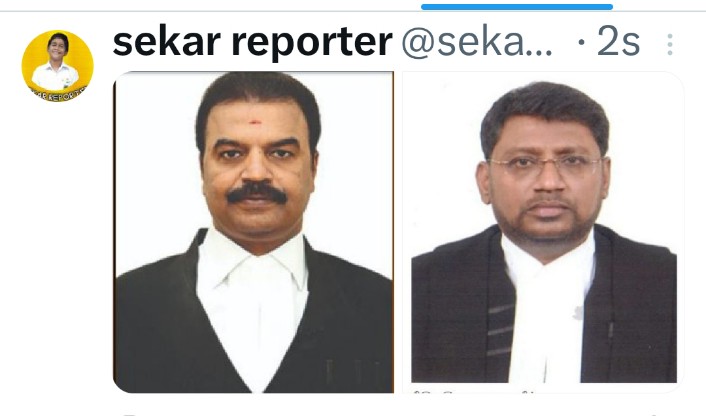

CORAM :

THE HON’BLE MR. JUSTICE R. MAHADEVAN

AND

THE HON’BLE MR. JUSTICE MOHAMMED SHAFFIQ

W.A.Nos.682 to 687 of 2023 and

W.P.No.7412 of 2023 and

other connected miscellaneous petitions

W.A.Nos.682 to 687 of 2023

1.The Tamil Nadu Public Service Commission,

Represented by its Secretary,

Public Service Commission Road, V.O.C.Nagar, Park Town, Chennai – 600 003.

2.The Controller of Examinations,

The Tamil Nadu Public Service Commission,

Public Service Commission Road, V.O.C.Nagar, Park Town, Chennai – 600 003.

…

The Chief Secretary,

Government of Tamil Nadu,

Human Resources Management Department,

Secretariat, Sr. George Fort, Appellants in

W.A.Nos.682, 683, 684, 685 and 687 of 2023 /

2nd and 3rd Appellants in

W.A.No.686 of 2023

Chennai – 600 009. … 1st Appellant in W.A.No.686 of 2023

Vs.

U.Kaviyarasan … Respondent in

W.A.No.682 of 2023

M.Saravana Kumar … Respondent in

W.A.No.683 of 2023

R.Satish … 1st Respondent in

W.A.No.684 of 2023

D.Dharmaraj … Respondent in

W.A.No.685 of 2023

V.Ramkumar … Respondent in

W.A.No.686 of 2023

A.Suganya … Respondent in

W.A.No.687 of 2023

Parkadhe Anibal KC … 2nd Respondent in

W.A.No.684 of 2023

Raja.D … 3rd Respondent in

W.A.No.684 of 2023

Praveen.D. … 4th Respondent in

W.A.No.684 of 2023

R.Sugadevan … 5th Respondent in

W.A.No.684 of 2023

(Respondents 2, 3, 4 and 5 are impleaded vide order dated 20.11.2023 passed in C.M.P.No.15792 of 2023 in W.A.No.684 of 2023)

Writ Appeals filed under Clause 15 of the Letters Patent, against the orders dated 20.03.2023 in W.P.Nos.7141 of 2023, 7486 of 2023, 7414 of 2023, 8059 of 2023, 7718 of 2023, 7934 of 2023 respectively.

For Appellants in

all Writ Appeals : Mr.J.Ravindran

Additional Advocate General

Assisted by Mr.I.Arbar Md.Abdullah

For Respondents : Mrs.Nalini Chidambaram, Senior Counsel

For Ms.C.Uma For 1st Respondent

in W.A.No.682 and 684 of 2023

Mr.R.Singaravelan

Senior Counsel For Respondents 2 to 5 in W.A.No.684 of 2023

Mr.R.Thamaraiselvan

For Mr.N.Kesavaraj for

Respondent in W.A.No.683 of 2023

Mr.T.Muthukrishnan

For Respondent in W.A.Nos.685 & 687/2023

* * *

W.P.No.7412 of 2023

D.Eraiyanbu … Petitioner Vs.

1.The Tamil Nadu Public Service Commission,

Rep. by its Secretary, TNPSC Road, V.O.C. Nagar, Chennai – 600 003.

2.The Controller of Examinations,

Tamil Nadu Public Service Commission, TNPSC Road, V.O.C.Nagar,

Park Town, Chennai – 600 003.

3.The State Director-cum-Commissioner,

Commissionerate of Welfare of the Differently Abled,

No.5, Kamarajar Salai, Lady Wellington College Campus, Chennai – 600 005. … Respondents

(R-3 suo motu impleaded vide order dated 20.03.2023 made in W.P.No.7412 of 2023)

Writ Petition is filed under Article 226 of the Constitution of India for issuance of a Writ of Mandamus, directing the respondents to call the petitioner with the register number 2701004040 for oral interview on 08.03.2023 or any other subsequent date and for counselling for the post of Assistant Engineer included in Combined Engineering Services pursuant to Notification No.10/2022 dated 04.04.2022 by including the register number of the petitioner in the list of Register numbers provisionally admitted to onscreen Certificate Verification for the posts in the Combined Engineering Services.

For Petitioner : Mrs.Nalini Chidambaram,

Senior Counsel

For Ms.C.Uma

For Respondents : Mr.J.Ravindran

Additional Advocate General Assisted by Mr.I.Arbar Md.Abdullah

* * *

COMMON JUDGMENT

(Judgment of the Court was delivered by R. MAHADEVAN, J.)

The writ appeals viz., WA.Nos.682 to 687 are directed against the three separate orders passed by the learned Judge on 20.03.2023 in W.P.Nos.7141,

7486 and 8059 of 2023; 7414 & 7934 of 2023; and 7718 of 2023.

2. The writ petition in WP.No.7412 of 2023 is filed for a direction to therespondents to call the petitioner with the register number 2701004040 for oral interview on 08.03.2023 or any other subsequent date for counselling for the post of Assistant Engineer included in the Combined Engineering Services, pursuant to notification No.10 of 2022, dated 04.04.2022 by including his register number in the list of Register numbers provisionally admitted to on-screen certificate verification for the posts in the Combined Engineering Services.

3. Since the issues involved in this batch of writ appeals and the writ petition are common, they are taken up for joint hearing and disposed of by this common judgment.

4. Brief facts which are necessary for disposal of all these matters are summarised as under:

4.1. The Tamil Nadu Public Service Commission (hereinafter referred to as “TNPSC”) issued Notification No. 10 of 2022 through Advertisement No. 613, dated 04.04.2022, inviting online applications until 03.05.2022 for direct recruitment to vacancies in various posts in the Combined Engineering Services. The written examination was conducted on 02.07.2022. Subsequently, based on the results of the written examination, a list of provisionally admitted candidates for on-screen certificate verification was published on the Commission’s website on 22.02.2023. However, the writ petitioners’ names were not included in the provisional list dated 22.02.2023. Instead, their names were placed in the list of rejected applications without any valid reason, leading them to file writ petitions.

4.2. The writ petitioners in W.P.Nos.7486, 8059, 7718, and 7934 of 2023 challenged the rejection of their online applications by approaching the writ court and sought to quash the same and consequently, direct the TNPSC to allow them to attend the oral test. Additionally, W.P.No.7141 of 2023 was filed for a direction to TNPSC to disclose the reasons for not including the petitioner’s register number and enable him to rectify the technical defects, if any, and permit him to attend oral test. Furthermore, W.P.No.7414 of 2023 was filed to direct the TNPSC to include the petitioner’s register number in the list of numbers provisionally admitted to on-screen certificate verification.

4.3. It was contended on the side of the TNPSC, in the course of writ proceedings that the writ petitioners’ applications were rejected because they had uploaded wrong documents, instead of essential documents. The details of the same are as under:

(i) The respondent in W.A.No.682 of 2023 (petitioner in W.P.No.7141 of

2023) claimed the benefit of PSTM (Persons Studied in Tamil Medium) reservation, but he has not uploaded the certificate to show that he had studied Classes XI and XII in Tamil, instead of that, uploaded the certificate to show that he had studied Classes IX and X in Tamil twice.

(ii) The respondent in W.A.No.683 of 2023 (petitioner in W.P.No.7486 of 2023) uploaded the Certificate of Class XII, instead of Community certificate.

(iii) The respondent in W.A.No. 685 of 2023 (petitioner in W.P.No.8059 of 2023) claimed the benefit of PSTM (Persons Studied in Tamil Medium) reservation but he has uploaded mark-sheets for Classes X and XII, instead of the certificate to show that he had studied Classes X and XII in Tamil.

(iv) The application of the respondent in W.A.No.684 of 2023 (petitioner in W.P.No.7414 of 2023) was rejected, as he has not uploaded his UG certificate, but has uploaded the consolidated mark statement of PG Course.

(v) The application of the respondent in W.A.No.687 of 2023 (petitioner in

W.P.No.7934 of 2023) was rejected as she had uploaded PG Certificate, instead of UG Certificate.

(vi) The application of the respondent in W.A.No.686 of 2023 (petitioner in W.P.No.7718 of 2023) was rejected on the ground tht he claimed to have studied from Class I to VIII in regular mode, but has not produced any supporting documents in respect of Classes I and II.

4.4. The learned Judge disposed of the writ petitions in W.P.Nos.7141,

7486 and 8059 of 2023 on 20.03.2023 with the following directions: –

“10. The upshot of the forgoing discussion is that the Writ Petitions are ordered on the following terms:-

(i) the Respondent shall forthwith inform through SMS, e-mail and publication in its official website to all those candidates (including the Petitioners) whose online applications have been rejected for failure to upload the required documents in support of their claim under the respective categories of reservation, to appear for oral interview along with originals of all required documents on specified dates for verification, and consider them for appointment as if their names had been included in the list of candidates provisionally admitted to on-screen certificate verification;

(ii) in the event of the said candidates failing to produce the required documents on the specified dates, they shall be treated as general candidates entitled to participate in the recruitment in open competition category;

(iii) the final result of the impugned recruitment shall be published only after carrying out the aforesaid exercise;

(iv) consequently, the connected miscellaneous petitions are closed; and

(v) there shall be no order as to costs.”

4.5. On the very same day, the learned Judge disposed of other two writ petitions viz., W.P.Nos.7414 and 7934 of 2023, in the same lines as that of the order in W.P.Nos.7141, 7486 and 8059 of 2023. However, there was a deviation in one aspect, with respect to direction no.(ii), which was replaced with the instruction that “in the event of the said petitioners fail to produce the required documents on the specified dates, their respective applications shall be treated as rejected for not producing proof for the required qualification for the post.” This modification was made, since these cases pertain to rejection of candidatures for not uploading the UG certificate. Similar W.P.No.7718 of 2023 came to be disposed of, on 20.03.2023, with the following direction:

“7. At the same time, such rejection of the application of the Petitioner would only disentitle him to claim the benefit of reservation under the category of persons who studied through Tamil Medium, but would not deprive him of the right to be treated as general candidate entitled to participate in the recruitment in open competition category. This would obviously mean that it is incumbent upon the Respondent to call upon the Petitioner through SMS, e-mail and publication in its official website to appear for oral interview along with all required documents on a specified date for verification, and consider him for appointment as if his name had been included in the list of candidates provisionally admitted to on-screen certificate verification. The final result of the impugned recruitment shall be published only after completing the aforesaid exercise.

In the result, the Writ Petition is disposed on the aforesaid terms. Consequently, the connected Miscellaneous Petitions are closed. No costs.”

4.6. Aggrieved by the three separate orders dated 20.03.2023 passed in the aforesaid writ petitions, the appellant authorities have come up with these writ appeals.

4.7. W.P.No.7412 of 2023 is filed by one D.Eraiyanbu, alleging that his candidature was rejected without assigning any reason. However, the same was not disposed of on 20.03.2023, along with the batch of other writ petitions, in view of the fact that the determination of his percentage of visual disability was pending; and the medical report confirming that the petitioner does not suffer from any visual disability was provided only on 28.03.2023. By the time, the batch of writ petitions had been disposed of on 20.03.2023. Hence, the learned Judge directed the Registry to post the writ petition along with this batch of writ appeals before this court.

5. Mr.J.Ravindran, learned Additional Advocate General assisted by

Mr.I.Arbar Md.Abdullah, learned standing counsel, appearing for the appellantTNPSC would submit that the respondents in W.A.No.682 and 685 of 2023 had claimed reservation under PSTM quota, however they had not uploaded the certificates to prove their claim, instead some other certificates were uploaded. Similarly, the respondent in W.A.No.683 of 2023 had claimed reservation under MBC category, however, he had not uploaded the required certificate. Hence, their applications were rejected. The learned Additional Advocate General further proceeded to refer to Clause 12(B)(iv)(v) and (vi) of the notification, which read as follows:

“(iv) If no such document as evidence for ‘PSTM’ is available, a certificate from the Principal / Head Master / District Educational Officer / Chief Educational Officer / District Adi Dravidar Welfare Officer / Controller of Examinations / Head / Director of Educational Institution / Director / Joint Director of Technical Education / Registrar of Universities, as the case may be, in the prescribed format must be uploaded at the time of submission of online application, for each and every educational qualification up to the educational qualification prescribed.

(v) Failure to upload such documents at the time of submission of online application as evidence for ‘Persons Studied in Tamil Medium’ for all 19 educational qualification up to the educational qualification prescribed, shall result in the rejection of candidature after due process.

(vi) Documents uploaded at the time of submission of online application as proof of having studied in Tamil medium, for the partial duration of any course / private appearance at any examination, shall not be accepted and shall result in the rejection of candidature after due process”.

Thus, according to the learned Additional Advocate General, the aforementioned clauses explicitly stipulate that the failure to upload the requisite documents as evidence for ‘Persons Studied in Tamil Medium’ (PSTM) will result in the rejection of the candidates’ applications and accordingly, the writ petitioners’ applications have been rejected.

5.1. It is further submitted by the learned Additional Advocate General appearing for the appellant – TNPSC that the respondents in W.A.Nos.684 and 687 of 2023, did not upload their UG certificate as required. Instead, they uploaded the mark-sheet for class XII and PG certificate, respectively, resulting in the rejection of their applications. To substantiate the said rejection, the learned Additional Advocate General has relied on Clauses 12 (I) and 12 (L) of the Notification, which state that any subsequent claims made after the initial online application will not be entertained and will be rejected. Furthermore, Clause 12 (L) addresses incomplete and incorrect applications, which are subject to summary rejection after due process. For better appreciation, the said Clauses

12 (I) and 12 (L) are reproduced below:

“12(I) – Evidence for all the claims made in the online application should he unloaded at the time of submission of online application. Any subsequent claim made after submission of online application will not be entertained. Failure to unload the documents at the time of submission of online application will entail rejection of application after due process”.

“12 (L) – Incomplete applications and applications containing wrong claims or incorrect particulars relating to category of reservation / eligibility / age /gender / communal category / educational qualification / medium of instruction / physical qualification / other basic qualifications and other basic eligibility criteria will be summarily rejected after due process”.

5.2. The learned Additional Advocate General appearing for the appellant – TNPSC submitted that the respondent in W.A.No. 686 of 2023 in his online application, had claimed that he underwent a regular course of study for Class I and II in Tamil medium. However, upon examining the records, it was found that the respondent had not studied Classes I and II in regular mode and had directly joined Class III without selecting the private study option, which was available while filling up the online application and hence, his application was rightly rejected.

5.3. The learned Additional Advocate General appearing for the appellant – TNPSC would also submit that online applications were called for on 04.04.2022 and the same could be submitted until 03.05.2022 at 11:59 PM and until 14.06.2022, online window was open for the candidates to verify and re-upload the certificates submitted when filling up the application form. Thus, when there was about 2 months time for the candidates to correct the errors flagged by the website against the certificates uploaded by the candidates, it is for them to utilise the time and correct the errors. In this regard, the learned Additional Advocate General placed reliance on Clause 15 of the Notification, which reads as follows:

“15. UPLOAD OF DOCUMENTS:-

(a) In respect of recruitment to this post, the candidates shall mandatorily upload the certificates / documents (in support of all the claims made / details furnished in the online application) at the time of submission of online application itself. It shall be ensured that the online application shall not be submitted by the candidates without mandatorily uploading the required certificates.

(b) The applicants shall have the option of verifying the uploaded certificates through their OTR. If any of the credentials have wrongly been uploaded or not uploaded or if any modifications are to be done in the uploading of documents, the applicants shall be permitted to edit and upload / re-upload the documents till two days prior to the date of hosting of hall tickets for that particular post (i.e. twelve days prior to the date of examination).

In the light of the above Clauses, the learned Additional Advocate General would submit that sufficient opportunities were given to the candidates to verify the uploaded certificates through their OTR and if any of the credentials have wrongly been uploaded or not uploaded or if any modifications are to be done in the uploading of documents, however, the respondent candidates failed to utilize the same, but approached the court by filing writ petitions.

5.4. In support of his contentions, the learned Additional Advocate General has relied on the following case laws:

(i) State of Tamil Nadu and Others vs. G. Hemalathaa and another

[2020 (19) SCC P.430]

“7. We havegiven our anxious consideration to the submissions made by the learned Senior Counsel for the Respondent. The Instructions issued by the Commission are mandatory, having the force of law and they have to be strictly complied with. Strict adherence to the terms and conditions of the Instructions is of paramount importance. The High Court in exercise of powers under Article 226 of the Constitution cannot modify/relax the Instructions issued by the Commission.

9. The High Court after summoning and perusing the answer sheet of the Respondent was convinced that there was infraction of the Instructions. However, the High Court granted the relief to the Respondent on a sympathetic consideration on humanitarian ground. The judgments cited by the learned Senior Counsel for the Respondent in Taherakhatoon (D) By Lrs v. Salambin Mohammed and Chandra Singh and others v. State of Rajasthan and Another in support of her arguments that we should not entertain this appeal in the absence of any substantial questions of law are not applicable to the facts of this case.

10. In spite of the finding that there was no adherence to the Instructions, the High Court granted the relief, ignoring the mandatory nature of the Instructions. It cannot be said that such exercise of discretion should be affirmed by us, especially when such direction is in the teeth of the Instructions which are binding on the candidates taking the examinations.

11. In her persuasive appeal, Ms. Mohana sought to persuade us to dismiss the appeal which would enable the Respondent to compete in the selection to the post of Civil Judge. It is a well-known adage that, hard cases make bad law. In Umesh Chandra Shukla v. Union of India, Venkataramiah, J., held that:

“13…. exercise of such power of moderation is likely to create a feeling of distrust in the process of selection to public appointments which is intended to be fair and impartial. It may also result in the violation of the principle of equality and may lead to arbitrariness. The cases pointed out by the High Court are no doubt hard cases, but hard cases cannot be allowed to make bad law. In the circumstances, we lean in favour of a strict construction of the Rules and hold that the High Court had no such power under the Rules.

12. Roberts, CJ. in Caperton v. A.T. Massey held that:

Extreme cases often test the bounds of established legal principles. There is a cost to yielding to the desire to correct the extreme case, rather than adhering to the legal principle. That cost has been demonstrated so often that it is captured in a legal aphorism: “Hard cases make bad law.”

13. After giving a thoughtful consideration, we are afraid that we cannot approve the judgment of the High Court as any order in favour of the candidate who has violated the mandatory Instructions would be laying down bad law. The other submission made by Ms. Mohana that an order can be passed by us under Article 142 of the Constitution which shall not be treated as a precedent also does not appeal to us.

14. In view of the aforementioned, the judgment of the High Court is set aside and the appeal is allowed.”

(ii) Sanjay Dixit vs State of U.P. [2019 (17) SCC 373]

11. Admittedly, the Rules governing the selection to the posts of Technician Grade 2 (Apprenticeship Electrical) require every candidate to submit a DOEACC certificate signifying completion of 80 hours’ CCC at the time of interview. Such condition was made compulsory. The advertisement also contained the condition regarding submission of the certificate at the time of interview. There is no doubt that there exists a power of relaxation of any of the Rules which could be exercised by the Chairman of the Corporation.

It is nobody’s case that the Chairman/Managing Director was not competent to relax the Rules. But, the submission made by the learned counsel for the writ petitioners is that the relaxation could not have been done as the advertisement did not mention about a possible relaxation of the Rules. We find force in the said submission made on behalf of the writ petitioners as this Court in Bedanga Talukdar [Bedanga Talukdar v. Saifudaullah Khan, (2011) 12 SCC 85 : (2011) 2 SCC (L&S) 635] held as follows : (SCC pp. 92-93, para 29)

“29. … In our opinion, it is too well settled to need any further reiteration that all appointments to public office have to be made in conformity with Article 14 of the Constitution of India. In other words, there must be no arbitrariness resulting from any undue favour being shown to any candidate. Therefore, the selection process has to be conducted strictly in accordance with the stipulated selection procedure. Consequently, when a particular schedule is mentioned in an advertisement, the same has to be scrupulously maintained. There cannot be any relaxation in the terms and conditions of the advertisement unless such a power is specifically reserved. Such a power could be reserved in the relevant statutory rules. Even if power of relaxation is provided in the rules, it must still be mentioned in the advertisement. In the absence of such power in the rules, it could still be provided in the advertisement.

However,the powerof relaxation, if exercised, has to be given due publicity. This would be necessary to ensure that those candidates who become eligible due to the relaxation, are afforded an equal opportunity to apply and compete. Relaxation of any condition in advertisement without due publication would be contrary to the mandate of equality contained in Articles 14 and 16 of the Constitution of India.”

(emphasis supplied)

12. We are in respectful agreement with the above judgment of this Court. Exercise of the power of relaxation without informing the candidates about the existence of such power would be detrimental to the interests of others who did not possess the certificate and did not take part in the selection process. We are unable to accept the submission that selection is on the basis of the performance of the candidates in the written test and interview and that the DOEACC certificate is not an essential requirement. The Rule as well as the advertisement provide for submission of the certificate at the time of interview, compulsorily. The Rule further provides for production of the certificate as an additional requirement for selection. The above stipulation in the Rule as well as the advertisement cannot be Ignored.

13. On the basis of the said findings, the point that remains to be considered is whether the High Court was right in upholding the relaxation in respect of candidates who submitted the certificate before 28-3-2012. The High Court took note of the fact that the certificates were not being issued by DOEACC to candidates who had already completed the course. The learned Division Bench of the High Court was of the opinion that there was a genuine problem and in the interest of those meritorious candidates who could not secure the certificate for no fault of theirs, they could not be penalised. The High Court placed reliance on the judgment of this Court in Amlan Jyoti Borooah v. State of Assam [Amlan Jyoti Borooah v. State of Assam, (2009) 3 SCC 227 : (2009) 1 SCC (L&S) 627] , SCC para 40 to support its view that relaxation can be done in larger public interest.

14. The question that then arises is whether the High Court could have granted such a relief after holding that the relaxation of the Rule could not have been made. The final relief in a case can be different from the ratio decidendi. It was held in Sanjay Singh v. U.P. Public Service Commission [Sanjay Singh v. U.P. Public Service Commission, (2007) 3

SCC 720 : (2007) 1 SCC (L&S) 870] as follows ; (SCC p. 732, para 10)

’10. ………. Broadly speaking, every judgment of superior courts has three segments, namely, (i) the facts and the point at issue; (ii) the reasons for the decision; and (iii) the final order containing the decision. The reasons for the decision or the ratio decidendi is not the final order containing the decision. In fact, in a judgment of this Court, though the ratio decidendi may point to a particular result, the decision (final order relating to relief) may be different and not a natural consequence of the ratio decidendi of the judgment. This may happen either on account of any subsequent event or the need to mould the relief to do complete justice in the matter. It is the ratio decidendi of a judgment and not the final order in the judgment, which forms a precedent.”

(emphasis supplied)

(iii) P.Prabu v. Tamil Nadu Public Service Commission

[W.A.No.4318 of 2019, dated 11.03.2020]

“Strict adherence to the terms and conditions of the instructions is paramount importance and the High Court in exercise of powers under Article 226 cannot modify/relax the instructions by the commission”

(iv) Bedanga Talukdar v. Saifudaullah Khan [2011) 12 SCC 85 :

(2011) 2 SCC (L&S) 635 : 2011 SCC OnLine SC 1325]

“29. We have considered the entire matter in detail. In our opinion, it is too well settled to need any further reiteration that all appointments to public office have to be made in conformity with Article 14 of the Constitution of India. In other words, there must be no arbitrariness resulting from any undue favour being shown to any candidate. Therefore, the selection process has to be conducted strictly in accordance with the stipulated selection procedure. Consequently, when a particular schedule is mentioned in an advertisement, the same has to be scrupulously maintained. There cannot be any relaxation in the terms and conditions of the advertisement unless such a power is specifically reserved. Such a power could be reserved in the relevant statutory rules. Even if power of relaxation is provided in the rules, it must still be mentioned in the advertisement. In the absence of such power in the rules, it could still be provided in the advertisement. However, the power of relaxation, if exercised,has to begiven due publicity. This would be necessary to ensure that those candidates who become eligible due to the relaxation, are afforded an equal opportunity to apply and compete. Relaxation of any condition in advertisement without due publication would be contrary to the mandate of equality contained in Articles 14 and 16 of the Constitution of India.

30. A perusal of the advertisement in this case will clearly show that there was no power of relaxation. In our opinion, the High Court committed an error in directing that the condition with regard to the submission of the disability certificate either along with the application form or before appearing in the preliminary examination could be. relaxed in the case of Respondent 1. Such a course would not be permissible as it would violate the mandate of Articles 14 and 16 of the Constitution of India.

32. In the face of such conclusions, we have little hesitation in concluding that the conclusion recorded by the High Court is contrary to the facts and materials on the record. It is settled law that there can be no relaxation in the terms and conditions contained in the advertisement unless the power of relaxation is duly reserved in the relevant rules and/or in the advertisement. Even if there is a power of relaxation in the rules, the same would still have to be specifically indicated in the advertisement. In the present case, no such rule has been brought to our notice. In such circumstances, the High Court could not have issued the impugned direction to consider the claim of Respondent 1 on the basis of identity card submitted after the selection process was over, with the publication of the select list.”

5.5. It is also submitted by the learned Additional Advocate General appearing for the appellant – TNPSC that when the writ appeals were taken up for hearing on 23.03.2023, this Bench permitted the appellant-TNPSC to conduct the full-fledged selection process, however, stayed the appointment alone. The operative portion of the order reads as follows:

“8. Concededly, theses cases are only in the admission stage and it is reported that today is the last date for publishing marks. Furthermore, the contempt petition, referred by the learned Additional Advocate General supra is not before us. In such perspective of the matter, we are of the view that the TNPSC shall be permitted to publish the marks, with a rider that appointments shall not be made with a view of the order dated 29.09.2022 of this court in Sub Appliation Nos.480 and 481 of 2022 in Contempt Petition No.615/2021. Needless to state that those, who were affected or aggrieved, are entitled to get themselves impleaded as parties to the present proceedings, when the matters are taken up for final hearing. The contention of Mrs.Nalini Chidambaram, learned Senior counsel that the entire process of selection, including Group Discussion and interview should be stalled, cannot be accepted and the said contention is rejected. A full-fledged selection process shall go on and appointment alone is stayed.”

Pursuant to the aforesaid order, the appellants have completed the entire selection process and they are awaiting the orders of this court for publishing the results. Stating so, the learned Additional Advocate General appearing for the appellants prayed to set aside the orders of the learned Judge and thereby allow all these writ appeals.

6. Mrs.Nalini Chidambaram, learned senior counsel representing Ms.C.Uma, learned counsel appearing for the respondents in W.A Nos.682 and 684 of 2023 would submit that there was a list published by the appellant-TNPSC stating the particulars of candidates whose online applications were rejected. Though it was stated that the reasons for rejection would be mentioned in the Annexure, no reasons were found in the Annexure itself. Consequently, candidates were arbitrarily thrown out from the selection process without being informed of the grounds for their rejection, which amounts to violation of the principles of natural justice. The learned senior counsel further submitted that the reasons for rejection pointed out by the TNPSC in the course of writ proceedings was that the respondent in W.A.No.682 of 2023 inadvertently uploaded the certificates certifying that he had studied Standards 9th and 10th in Tamil twice instead of uploading certificates certifying that he had studied Standards 11th and 12th in Tamil. With regard to the respondent in W.A.No.684 of 2023, by mistake he had uploaded PG certificate, instead of UG certificate. According to the learned senior counsel, the respondents have fully qualified for the post in question and hence, the rejection of their candidature for want of production of documents, which is purely procedural in nature, is unsustainable. Even as per the Notification, the same can be done only by following due process and not unilaterally without affording any opportunity to them. Taking note of the same in proper perspective, the learned Judge has given direction to the appellant TNPSC to the effect that opportunity to produce documents be given not just to the candidates, who are before the Court, but also to all the candidates whose candidatures have been rejected, by the orders impugned herein, which need not be interfered with by this court.

6.1. Adding further, Mr.R.Thamaraiselvan, learned counsel representing

Mr.N.Kesavaraj, learned counsel appearing for the respondent in W.A.No. 683 of 2023, by relying upon Clause 12(L) of the Notification, would submit that incomplete applications should be rejected after following due process of law, however, no such process was followed in this case. The learned counsel would also contend that the claim made in the online application for the recruitment will be taken into consideration as per Clause 12 (M) of the Notification and in this case, the respondent claimed that he belongs to MBC Community and however, instead of uploading community certificate, 12th certificate was uploaded. The learned counsel would further assert that the respondent did not provide false information and is willing to produce the community certificate during physical verification. Furthermore, the learned counsel referring to Clause 15(B) of the Notification, pointed out that modifications can be made up to 12 days before the examination date. However, due to a technical glitch in the TNPSC’s document upload software, the respondent was unable to upload the required documents within the stipulated time. That apart, the learned counsel submitted that TNPSC allowed the candidates in Group IV and Group I examinations to rectify certificate issues within a 2-day window through Press Releases 45/2023 and 50/2023, however, this opportunity was not provided to the respondent. It is also submitted that when an identical issue came up for consideration, in the case of direct recruitment to the posts of VAOs, in which the appellant (TNPSC) invited applications through online mode, a Division Bench of this Court in its judgement in The Secretary, TNPSC Vs. J. Thamizhisai and Others [2011 (3) MLJ] dismissed the writ appeal filed by the TNPSC and affirmed the order of the learned Judge. The relevant passage of the said judgment is profitably reproduced below:

“ 7. As far as the Petitioner is concerned, she had produced the original certificate at the time of Certificate Verification. As such, relying of Clause 15, the Commissions’ arguments cannot be accepted and apart form this, as per the judgment of the Division Bench (Madurai) in W.A.No.585 of 2009 by order dated 11.11.2009, the Division Bench has held that certain certificates are to be treated as important on which relate to the academic qualification but as far as other certificates including Community Certificates are concerned, the non-production with the application and before the provisional selection is finalized, if those certificates are produced, the same should be accepted. For the reasons stated above, I am of the opinion that the Petitioner is entitled to succeed. Hence, the Impugned order is set aside and the Writ Petition is allowed.”

6.2. Continuing further, Mr.T.Muthukrishnan, learned counsel appearing for the respondents in W.A.Nos. 685 and 687 of 2023, would submit that the respondent in W.A.No.685 of 2023 had uploaded the mark sheet for Classes X and XII, instead of the required PSTM certificate for Classes X and XII. Similarly, the respondent in W.A.No.687 of 2023 had uploaded her PG Certificate instead of the required UG Certificate. As a result of these errors, the applications of the respondents were rejected. It is further contended that on 13.01.2023, the results were published on the basis of 1:3 ratio (Selection list 1), which included the respondents’ names. However, on 22.02.2023, the TNPSC published a revised 1:2 ratio list (Selection list 2), and in this updated result, the respondents’ names were not found and their names were found in the annexure list stating that “rejected for various reasons”, which according to the learned counsel, is against the principles of natural justice. Referring to the decision in State of Orissa Vs.

Binapani Dei [AIR 1967 SC 1269] it is emphasized that any administrative decision with adverse civil consequences must adhere to the rules of natural justice. This entails informing the person concerned of the case against them and providing an opportunity to be heard for the purpose of explaining or defending their position. It is also submitted that some candidates with lower marks were selected, while the respondents were rejected without being given a fair opportunity to rectify their mistakes. Furthermore, it is highlighted by the learned counsel that the respondents come from remote villages and are first-generation candidates and if the appeals are allowed, they will be put to irreparable loss and hence, their cases may be considered leniently.

7. In reply, the learned Additional Advocate General appearing for the appellants would submits that a small number of candidates attempt to circumvent the established rules and regulations for document submission in TNPSC examinations by seeking court orders at the eleventh hour, when mistakes are on the part of the writ petitioners/respondents, and the results are being published. The learned Additional Advocate General would further submit that the TNPSC, as an institution, takes its commitment to transparency, fairness, and integrity very seriously. One of the fundamental tenets of this commitment is the strict adherence to the prescribed guidelines, including the submission of required documents within the time prescribed. When the individuals resort to legal intervention to bypass prescribed procedures, it not only disrupts the application process, but also sets a dangerous precedent that can lead to chaos and an inundation of court cases. Hence, the learned Additional Advocate would submit that no leniency should be shown to the respondents/writ petitioners in enforcing these rules.

8. Mr.R.Singaravelan, learned senior counsel appearing for the respondents 2 to 5 in WA.No.684 of 2023 would submit that they are the selected candidates waiting for appointment and they are sailing with the appellants. It is submitted by the learned senior counsel that the order of stay granted in favour of the appellants has to be vacated for three reasons viz., (i) it amounts to tinkering with the brochure, because while the brochure makes it clear that submission of incorrect or incomplete documents would be met with the rejection, this Court ought not to have stopped the authorities from acting according to Clauses 15 and 16 of the Notification; (ii)not only once, but thrice the candidates were given opportunity to produce documents, but they did not choose to avail the same and it is settled law that the courts would not come to the rescue of those who sleep over their rights. The learned senior counsel further submitted that as per the notification, the writ petitioners were required to submit their proper mark sheets and educational qualification certificates and the failure to do so would result in the forfeiture of their opportunity for selection. In other words, the candidates are not only bound by the notification, but also estopped from challenging their nonselection for violation of the notification norms, as held by the Apex Court in K.A.Nagamani vs. Indian Airlines and others [2009 (5) SCC 515], in

which, it was held as follows:

“53. Yet another aspect of the matter that the appellant admittedly had participated in the similar selection process for erstwhile Grades 15 and 16 Manger(Maintenance/ System) and Senior Manager (Maintenance / Systems) respectively. The Corporation had given adequate opportunity to the appellant to compete with all eligible candidates at the selection for consideration of the case of all eligible candidates to the post in question.

54. The Corporation did not violate the right to equality “guaranteed under Articles 14 and 16 of the constitution. The appellant having participated in the selection process along with the contesting respondents without any demur or protest cannot allowed to turn round and question the very same process having failed to qualify for the promotion”.

and (iii) If at all any relief was deemed fit to be awarded by the Court, the same must have been restricted just to those who come to Court and not in an omnibus fashion to all similarly placed persons. This amounts to treating a service matter as a Public Interest Litigation, which is time and again criticised by the Apex Court right from Duryodhana Sahu (Dr) v. Jitendra Kumar Mishra [1998 7 SCC

273] wherein, it was observed as follows:

“The Constitution of Administrative Tribunals was necessitated because of the large pendency of cases relating to service matters in various courts in the country. It was expected that the setting up of administrative tribunal to deal exclusively in service matters would go a long way in not only reducing the burden of the courts but also provide to the persons covered by the Tribunals speedy relief in respect of their grievances. The basic idea as evident from the various provisions’ of the act is that the tribunal should guickly. redress the grievance in relation to service matters. The definition of service matters found in section 3(q) shows that in relation to a person, the expression means all service matters relating to the condition of his service. The significance of the word ”his” cannot be ignored. Section 3(b) defines the word “Application” as an application made under section 19. The latter section refers to “Person Aggrieved”. In order to bring a matter before the Tribunal, an application has to be made and the same can be made only by a person aggrieved by any order pertaining to any- matter within the jurisdiction of the Tribunal. The word “Order” has been defined in the explanation to sub-section (1) of section 19 so that all mattes referred to in section 3(q) as service matter could be brought before the Tribunal. If in that context sections 14 and 15 are read, there is no doubt that a private citizen or a stranger having no existing right to any post and not intrinsically concerned with any service matter is not entitled to approach the Tribunal. If public interest litigations at the instance of strangers are allowed to be entertained by the Tribunal, the very object of speedy disposal of service matters would get defeated. There is no substance in the contention that the proceedings before the Tribunal are in the nature of quo warranto and it could be filed by any member of the public as he is an aggrieved person in the sense public interest is affected. The Applications in the present case have been filed before the appointment of the petitioner as a lecturer and the relevant prayers are to quash the creation of the post itself and preventing the authorities from appointing the petitioner as a lecturer. Hence, the applications filed by the respondents cannot be considered to be in the nature of quo warranto”.

8.1. The learned senior counsel for the respondents 2 to 5 in WA No.684 of 2023 would also submit that strict adherence to the terms and conditions mentioned in the notification is paramount consideration and the same cannot be relaxed. In support of his contention, the learned senior counsel has referred to the judgment of this court in Dr.M.Vennila Vs. Tamil Nadu Public Service Commission [2006 (3) CTC 449], wherein, it was held as follows:

“ 25. In the earlier part of our order, we have extracted relevant provision, viz., Instructions, etc. to Candidates as well as the Information Brochure of the Tamil Nadu Public Service Commission, we hold that the terms and conditions of Instructions, etc. to Candidates and Information Brochure have the force of law and have to be strictly complied with. We are also of the view that no modification/relaxation can be made by the Court in exercise of powers under Article 226 of the Constitution of India and application filed in violation of the Instructions, etc. to Candidates and the terms of the Information Brochure is liable to be rejected. We are also of the view that strict adherence to the terms and conditions is paramount consideration and the same cannot be relaxed unless such power is specifically provided to a named authority by the use of clear language. As said at the beginning of our order, since similar violations are happening in the cases relating to admission of students to various courses, we have dealt with the issue exhaustively. We make it clear that the above principles are applicable not only to applications calling for employment, but also to the cases relating to the admission of students to various courses. We are constrained to make this observation to prevent avoidable prejudice to other applicants at large.”

8.2. It is further submitted by the learned senior counsel apeparing for the respondents 2 to 5 in WA No.684 of 2023 that pursuant to the interim order dated 23.03.2023, the respondents herein were not issued with the orders of appointment to the post of Assistant Engineers and suffered even after they got selected by competing with more than 35000 candidates those who have

participated in the said selection process. Hence, the learned senior counsel prays for appropriate orders in this writ appeal.

9. Mrs.Nalini Chidambaram, learned senior counsel representing Ms.C.Uma, learned counsel for the petitioner in W.P.No.7412 of 2023 submitted that the petitioner’s candidature should be considered as that of a general candidate rather than as a visually disabled candidate. Whereas, the learned Additional Advocate General appearing for the TNPSC raised objection to the same, stating that if such an opportunity is granted, it would open the floodgates for every individual, who has made a mistake to approach the court and seek correction, even when the mistake is on his / her part.

10. Heard the submissions made by all the parties and also perused the materials available on record.

11. The point of dispute in all the cases before us can be categorized into the following categories:

(i) The PG Degree Certificate has been uploaded instead of UG Certificate,

(ii) The PSTM Certificates for the entire period of study have not been uploaded

(iii) Uploading of Class XII Certificate instead of Community

Certificate

(iv) Verification of Visual Disablement Claim

12. Before proceeding to decide the appeals, it is necessary to look into the notification and the conditions. The notification for direct recruitment in Combined Engineering Services was issued on 04.04.2022, prescribing the last date of submission of the application on 03.05.2022. The instructions to candidates have been amended and come into force with effect from 22.03.2022. Originally, the examination was scheduled to be conducted on 26.06.2022.

However, the date was modified and the examinations were held on 02.07.2022. The oral interview was scheduled to be held between 08.03.2023 and 23.03.2023.

13. The relevant clauses in the Notification for recruitment dated 04.04.2022 are extracted below, for better understanding:

WARNING

Sl No 5. In respect of recruitment to this post, the applicants shall mandatorily upload the certificates / documents (in support of all the claims made / details furnished in the online application) at the time of submission of online application itself. It shall be ensured by the applicants that the online application shall not be submitted without uploading the required certificates.

3. IMPORTANT DATES AND TIME:

Date of Notification 04.04.2022

Last date for submission of online application 03.05.2022

Dates of written examinations

Paper-I: Subject Paper (Degree Standard) 26.06.2022 12.30 p.m. 09.30 a.m. to

Date of Notification 04.04.2022

Paper-II:

Part-A

Tamil Eligibility Test (SSLC Standard)

Part-B

General Studies (Degree Standard) 26.06.2022 05.00 p.m. 02.00 pm. to

The Examinations were subsequently postponed to 02.07.2022 by Notification No. 10A dated 28.04.2022. ( Emphasis added)

4. QUALIFICATIONS

(B)EDUCATIONAL QUALIFICATION (as on 04.04.2022)

Applicants should possess the following or its equivalent qualification awarded by any University or Institution recognized by the University Grants Commission/AICTE as the case may be.

TABLE (Not Extracted in this judgement but the contents will be discussed in the later part of the judgment)

12. GENERAL INFORMATION:

(A) The rule of reservation of appointments is applicable to this recruitment separately for each post.

(B)

(ii) Candidates claiming to be Persons studied in Tamil Medium (PSTM) must upload the document at the time of submission of online application for the same in the form of SSLC, HSC, Transfer Certificate, Provisional Certificate, Convocation Certificate, Degree Certificate, PG

Degree Certificate, Mark Sheets, Certificate from the Board or University or

from the Institution, as the case may be, with a recording that he/she had studied the entire duration of the respective course(s) through Tamil Medium of instruction.

(iii) Candidates must upload documents at the time of submission of online application as evidence of having studied in the Tamil medium, all educational qualification upto the educational qualification prescribed

(iv) If no such document as evidence for ‘PSTM’ is available, a certificate from the Principal / Head Master / District Educational Officer / Chief Educational Officer / District Adi Dravidar Welfare Officer / Controller of Examinations / Head / Director of Educational Institution / Director / Joint Director of Technical Education / Registrar of Universities, as the case may be, in the prescribed format must be uploaded at the time of submission of online application, for each and every educational qualification up to the educational qualification prescribed

(v) Failure to upload such documents at the time of submission of online application as evidence for ‘Persons Studied in Tamil Medium’ for all educational qualification up to the educational qualification prescribed, shall result in the rejection of candidature after due process.

(vi) Documents uploaded at the time of submission of online application as proof of having studied in Tamil medium, for the partial duration of any course / private appearance at any examination, shall not be accepted and shall result in the rejection of candidature after due process.

(I) Evidence for all the claims made in the online application should be uploaded at the time of submission of online application. Any subsequent claim made after submission of online application will not be entertained. Failure to upload the documents at the time of submission of online application will entail rejection of application after due process.

(L)Incomplete applications and applications containing wrong claims or incorrect particulars relating to category of reservation / eligibility / age /gender / communal category / educational qualification / medium of instruction / physical qualification / other basic qualifications and other basic eligibility criteria will be summarily rejected after due process.

13. OTHER IMPORTANT INSTRUCTIONS:

(a) Applicants should ensure their eligibility for the examination. Before applying for / appearing for the examination, the applicants should ensure their eligibility for such examination and that they fulfil all the conditions in regard to age, educational qualifications, number of chances for fee concession, etc., as prescribed by the Commission’s notification. Their admission to all stages of the examination will be purely provisional, subject to their satisfying the eligibility conditions. Mere admission to the written examination / certificate verification / oral test / counselling or inclusion of name in the selection list will not confer on the candidates any right to appointment. The candidature is therefore, provisional at all stages and the Commission reserves the right to reject candidature at any stage after due process, even after selection has been made, if a wrong claim or violation of rules or instructions is confirmed.

(g) Unless specific instruction is given, applicants are not required to submit along with their application any certificates (in support of their claims regarding age, educational qualifications, physical qualification, community, physical disability etc.,) which should be submitted when called for by the Commission. Applicants applying for the examination should ensure that they fulfil all the eligibility conditions for admission to the examination. Their admission at all the stages of examination for which they are admitted by the Commission will be purely provisional, subject to their satisfying the prescribed eligibility conditions. If, on verification at any time before or after the written examination /certificate verification / oral test, it is found that they do not fulfil any of the eligibility conditions, their candidature for the recruitment will be summarily rejected after due process.

Clause 14.

9. The applicants shall be permitted to edit the details in the online application till the last date stipulated for submission of online application. After the last date for submission of online applications, no modification shall be permitted in respect of the application data i.e., the details furnished by the candidates in the online application.

10. ….

c) Applicants need not send the printout of the online application

or any other supporting documents to the Commission.

15. UPLOAD OF DOCUMENTS:

(a) In respect of recruitment to this post, the candidates shall mandatorily upload the certificates / documents (in support of all the claims made / details furnished in the online application) at the time of submission of online application itself. It shall be ensured that the online application shall not be submitted by the candidates without mandatorily uploading the required certificates.

(b) The applicants shall have the option of verifying the uploaded certificates through their OTR. If any of the credentials have wrongly been uploaded or not uploaded or if any modifications are to be done in the uploading of documents, the applicants shall be permitted to edit and upload / re-upload the documents till two days prior to the date of hosting of hall tickets for that particular post (i.e. twelve days prior to the date of examination)

16. Online application can be submitted / edited upto 03.05.2022 till 11.59 p.m., after which the link will be disabled and the uploaded documents can be re-uploaded upto 14.06.2022 till 11.59 P.M.

ANNEXURE – V

Sl. No 3. – Educational Qualification (Provisional Certificate /

Degree Certificate / Consolidated Mark Sheet)

1. Diploma Certificate

2. Post Diploma Certificate

3. U.G. Degree in Engineering

4. P.G. Degree in Engineering 5. Apprenticeship Training Certificate

Note:

If the issue date of provisional certificate / U.G. Degree / P.G. Degree Certificate / Diploma falls after the date of notification (i.e 04.04.2022) candidates should upload evidence for having acquired the prescribed qualification on or before the date of Notification, failing which their applications will be rejected.”

14. The Relevant clauses in the Instructions to the applicants as modified with effect from 20.03.2022 are as follows:

Instructions to applicants

13 B. The original certificates in support of the claims made in the online application, should be scanned and uploaded for onscreen certificate verification, during the period stipulated by the Commission, failing which candidature is liable to be summarily rejected after due process.

14 G. Educational Qualification

(vi) Candidates claiming possession of qualification higher than that prescribed for a post, must upload / produce certificates, issued on / before the date of notification, in support of such claim. Failure to upload / produce such certificates shall result in rejection of candidature after due process

(viii) In any case, the educational qualification prescribed, should have been obtained in the order as specified in Section 25 of the Tamil Nadu Government Servants (Conditions of Service) Act, 2016 and as stated at (i) to (iii) of Explanation-I of Paragraph 9 of these Instructions.

(ix) In cases where the duration of the prescribed educational / technical course has been specified in the notification, any discrepancy between the claim in the application and the documents uploaded / produced, shall result in the rejection of candidature after due process.

(xii) Claim to possess educational qualification unsupported by the prescribed documents shall result in rejection of candidature after due process.

Clause 14 R

(ii). Candidates claiming to be Persons studied in Tamil Medium

(PSTM) must upload / produce evidence for the same, in the form of SSLC,

HSC, Transfer Certificate, Provisional Certificate, Convocation Certificate,

Degree Certificate, PG Degree Certificate, Mark Sheets, Certificate from the Board or University or from the Institution, as the case may be, with a recording that he had studied the entire duration of the respective course(s) through Tamil medium of instruction.

(iv) If no such document as evidence for ?Person Studied in Tamil

Medium‘ is available, a certificate from the Principal / Head Master / District

Educational Officer / Chief Educational Officer / District Adi Dravidar Welfare Officer / Registrar / Controller of Examinations / Head / Director of the Educational Institution / Director / Joint Director of Technical Education/ Registrar of Universities as the case may be, in the format as given below must be uploaded / produced, for each and every educational qualification upto the educational qualification prescribed.

(v) Failure to upload / produce such documents as evidence for ?Persons Studied in Tamil Medium‘ for all educational qualification upto the educational qualification prescribed, shall result in the rejection of candidature after due process.

(vi) Documents uploaded / produced as proof of having studied in Tamil medium, for the partial duration of any course / private appearance at any examination, shall not be accepted and shall result in the rejection of candidature after due process.

Post script

The instructions contained herein are general in nature. Instructions

specific to individual recruitments are issued in the respective notifications, memoranda of admission (hall tickets), question booklets, answer sheets/question-cum- answer booklets and examination centres.

15. The instructions with effect from 22.03.2022 have been subsequently amended. The amendments are not applicable as the instructions that were in vogue as on 04.04.2022, the date of notification are alone applicable. For the modified instructions to apply, the notification would also have to be issued afresh. Further, it is also evident that the instructions are general in nature and the notifications are specific with regard to the posts to be filled up. Therefore, the notification and the instructions have to be harmoniously read together with preference to the terms and conditions in the notification.

16. Now coming to the notification, it contains clauses relating to eligibility, requirement of submission of documents to prove the claim, documents required to fulfil the qualifications, documents required to satisfy the claim under horizontal reservation, conduct during the examination, selection process, reservation, fees and other matters. The notification also explicitly makes it clear that the candidate must be eligible as on the date of notification. Clause 13 (g) clearly states that if the candidates do not fulfil any of the eligibility conditions upon verification of the certificates, then their candidature would be rejected. The clause also states that the documents must be produced when called for. Therefore, all that is required for an applicant to be considered is that he must fulfil all the eligibility conditions on the date of notification; and what is also relevant from various clauses in the notification is that when the documents are not furnished, the candidature can be rejected after due process.

16.1. Once, the applicants have satisfied all the eligibility conditions, their candidature is not to be ordinarily rejected for want of proof, when the notification itself permits production of proof at a later date. It would be useful to refer to the judgment of the Apex Court in Charles K. Skaria v. C. Mathew (Dr), [(1980)

2 SCC 752 : 1980 SCC (L&S) 305], wherein, it was held as follows:

“20. There is nothing unreasonable or arbitrary in adding 10 marks for holders of a diploma. But to earn these extra 10 marks, the diploma must be obtained at least on or before the last date for application, not later. Proof of having obtained a diploma is different from the factum of having got it. Has the candidate, in fact, secured a diploma before the final date of application for admission to the degree course? That is the primary question. It is prudent to produce evidence of the diploma along with the application, but that is secondary. Relaxation of the date on the first is illegal, not so on the second. Academic excellence, through a diploma for which extra mark is granted, cannot be denuded because proof is produced only later, yet before the date of actual selection. The emphasis is on the diploma; the proof thereof subserves the factum of possession of the diploma and is not an independent factor. The prospectus does say:

“(4)(b) 10% to diploma holders in the selection of candidates to M.S., and M.D., courses in the respective subjects or sub-specialities.

13. Certificates to be produced: In all cases true copies of the following documents have to be produced:

(k) Any other certificates required along with the application.”

This composite statement cannot be read formalistic fashion. Mode of proof is geared to the goal of the qualification in question. It is subversive of sound interpretation and realistic decoding of the prescription to telescope the two and make both mandatory in point of time. What is essential is the possession of a diploma before the given date; what is ancillary is the safe mode of proof of the qualification. To confuse between a fact and its proof is blurred perspicacity. To make mandatory the date of acquiring the additional qualification before the last date for application makes sense. But if it is unshakeably shown that the qualification has been acquired before the relevant date, as is the case here, to invalidate this merit factor because proof, though indubitable, was adduced a few days later but before the selection or in a manner not mentioned in the prospectus, but still above-board, is to make procedure not the handmaid but the mistress and form not as subservient to substance but as superior to the essence.

21. Before the Selection Committee adds special marks to a candidate based on a prescribed ground it asks itself the primary question: has he the requisite qualification? If he has, the marks must be added. The manner of proving the qualification is indicated and should ordinarily be adopted. But, if the candidate convincingly establishes the ground, though through a method different from the specified one, he cannot be denied the benefit. The end cannot be undermined by the means. Actual excellence cannot be obliterated by the choice of an incontestable but unorthodox probative process. Equity shall overpower technicality where human justice is at stake.

***

26. Even so, there is a snag. Who are the diploma-holders eligible for 10 extra marks? Only those who, at least by the final date for making applications for admissions possess the diploma. Acquisition of a diploma later may qualify him later, not this year. Otherwise, the dateline makes no sense. So, the short question is when can a candidate claim to have got a diploma? When he has done all that he has to do and the result of it is officially made known by the authority concerned. An examinee for a degree or diploma must complete his examination—written, oral or practical—before he can tell the Selection Committee or the court that he has done his part. Even this is not enough. If all goes well after that, he cannot be credited with the title to the degree if the results are announced only after the last date for applications but before selection. The second condition precedent must also be fulfilled viz. the official communication of the result beforethe selectionand its being brought to the ken of the committee in an authentic manner. May be, the examination is cancelled or the marks of the candidates are withheld. He acquires the degree or diploma only when the results are officially made known. Until then his qualification is inchoate. But once these events happen his qualification can be taken into account in evaluation of equal opportunity provided the Selection Committee has the result before it at the time of—not after—the selection is over. To sum up, the applicant for postgraduate degree course earns the right to the added advantage of diploma only if (a) he has [Ed.: Matter between two asterisks is emphasised in original.] completed the diploma examination on or before the last date for the application [Ed.: Matter between two asterisks is emphasised in original], (b) the result of the examination is also published before that date, and (c) the candidate’s success in the diploma course is brought to the knowledge of the Selection Committee before completion of selection in an authentic or acceptable manner. The prescription in the prospectus that a certificate of the diploma shall be attached to the application for admission is directory, not mandatory, a sure mode, not the sole means. The delays in getting certified copies in many departments have become so exasperatingly common that realism and justice forbid the iniquitous consequence of defeating the applicant if, otherwise than by a certified copy, he satisfies the committee about his diploma. There is nothing improper even in a Selection Committee requesting the universities concerned to inform them of the factum and get the proof straight by communication therefrom—unless, of course, this facility is arbitrarily confined only to a few or there is otherwise some capricious or unveracious touch about the process.”

16.2. Reiterating the above view, the Hon’ble Apex Court in Dheerender Singh Paliwal v. UPSC, [(2017) 11 SCC 276 : (2018) 1 SCC (L&S) 318]

held as follows:

“11. We heard Mr V. Shekhar, learned Senior Counsel for the appellant who drew our attention to the various interviews narrated above which are part of our record and also relied upon the decision of this Court in Charles K. Skaria v. C. Mathew [Charles K. Skaria v. C. Mathew, (1980) 2 SCC 752 : 1980 SCC (L&S) 305] wherein this Court has held as under in paras 21 & 26: (SCC pp. 762 & 764)

“21. Before the Selection Committee adds special marks to a candidate based on a prescribed ground it asks itself the primary question: has he the requisite qualification? If he has, themarks mustbe added. The manner of proving the qualification is indicated and should ordinarily be adopted. But, if the candidate convincingly establishes the ground, though through a method different from the specified one, he cannot be denied the benefit. The end cannot be undermined by the means. Actual excellence cannot be obliterated by the choice of an incontestable but unorthodox probative process. Equity shall overpower technicality where human justice is at stake.

***

26. Even so, there is a snag. Who are the diploma-holders eligible for 10 extra marks? Only those who, at least by the final date for making applications for admissions possess the diploma. Acquisition of a diploma later may qualify him later, not this year. Otherwise, the dateline makes no sense. So, the short question is when can a candidate claim to have got a diploma? When he has done all that he has to do and the result of it is officially made known by the authority concerned. An examinee for a degree or diploma must complete his examination—written, oral or practical—before he can tell the Selection Committee or the court that he has done his part. Even this is not enough. If all goes well after that, he cannot be credited with the title to the degree if the results are announced only after the last date for applications but before selection. The second condition precedent must also be fulfilled viz. the official communication of the result before the selection and its being brought to the ken of the committee in an authentic manner. May be, the examination is cancelled or the marks of the candidates are withheld. He acquires the degree or diploma only when the results are officially made known. Until then his qualification is inchoate. But once these events happen his qualification can be taken into account in evaluation of equal opportunity provided the Selection Committee has the result before it at the time of—not after—the selection is over. To sum up, the applicant for postgraduate degree course earns the right to the added advantage of diploma only if (a) he has [Ed.: Matter between two asterisks is emphasised in original.] completed the diploma examination on or before the last date for the application [Ed.: Matter between two asterisks is emphasised in original.] , (b) the result of the examination is also published before that date, and (c) the candidate’s success in the diploma course is brought to the knowledge of the Selection Committee before completion of selection in an authentic or acceptable manner. The prescription in the prospectus that a certificate of the diploma shall be attached to the application for admission is directory, not mandatory, a sure mode, not the sole means. The delays in getting certified copies in many departments have become so exasperatingly common that realism and justice forbid the iniquitous consequence of defeating the applicant if, otherwise than by a certified copy,he satisfiesthe committee about his diploma. There is nothing improper even in a Selection Committee requesting the universities concerned to inform them of the factum and get the proof straight by communication therefrom—unless, of course, this facility is arbitrarily confined only to a few or there is otherwise some capricious or unveracious touch about the process.”

(emphasis supplied)

14. Having considered the respective submissions and having noted the dictum of this Court as noted above, we are of the view that in the light of the prescription noted in the advertisement, the particulars furnished by the appellant in response to the said advertisement and the production of the degree certificate for having secured the BSc degree with Zoology as the subject at a later point of time there was substantial compliance with the requirement to be fulfilled in the matter of the essential qualifications possessed by the appellant. Therefore, applying the principle set down by this Court, the respondent Commission ought to have considered the application and more so when the appellant was already in the services of the Forensic Science Laboratory as Senior Scientific Assistant and his essential qualifications were very much on record in the form of résumé and therefore pursuant to the direction of the Tribunal when the respondent Commission interviewed the appellant and found him fit to be selected and appointed for the post of Senior Scientific Officer in all fairness should have appointed the appellant.

15. In the first place, it must be stated that it is not a case of the appellant not possessing the required essential qualifications but was of only not enclosing the certificate in proof of the added qualification of Zoology as one of the subjects at BSc level, from a recognised University. In the application when once the appellant, marked ‘1’ against Column 9 and thereby confirmed that he possesses the essential qualification, namely, the postgraduate qualification as well as the degree level qualification, if at all there was any doubt about any of the qualification, the appellant should have been called upon to produce the required certificate in proof of such essential qualification. In fact in this context, when we refer to the interview proceedings of the appellant as well as two other candidates we find that the appellant produced the original BSc/MSc degree in Zoology and also submitted the attested photocopy of BSc Zoology degree. The outcome of the said interview was that the appellant should be cleared of his selection. Insofar as other two candidates, namely, Miss Babyto and Miss Imrana, are concerned, we find that the production of their caste certificate was not in the prescribed pro forma initially, nevertheless those candidates were allowed to produce the original caste certificate issued by the competent authority and after verifying the same by accepting the attested photocopies of such caste certificates, their cases were cleared. Therefore, when such a course was adopted by the respondent Commission in regard to those two candidates there is no reason why the candidature of the appellant alone was kept in suspension, though he also cleared interview process. Even assuming such clearance was not made awaiting the outcome of the order of the Tribunal, when the Tribunal upheld his selection and directed the respondent to issue necessary orders for appointment, in all fairness the respondent Commission should have issued the order of appointment. We are of the view that such an approach of the respondent Commission was unfair having regard to the very trivial issue, namely, a non-production of an added qualification as part of the essential qualification at the degree level which the appellant did possess and for mere asking, the appellant could have readily produced the same through his employer.

16. We are therefore convinced that the interference with the order of the Tribunal by the Division Bench was uncalled for and accordingly while setting aside the impugned judgment

[UPSC v. Dheerender Singh Paliwal, 2010 SCC OnLine Del 3465 : (2010)

119 DRJ 662] of the Division Bench of the High Court, the order of the

Tribunal dated 9-12-2009 [Dheerender Singh Paliwal v. UPSC, 2009 SCC OnLine CAT 1593] stands restored. The appeal is allowed. The appellant shall be appointed as Senior Scientific Officer as directed in the aforesaid order and shall be granted all the benefits including restoration of the seniority as on the date of the appointment of any of his juniors in the said position pursuant to the selection made in the Advertisement dated 28-2-2009 to 6-3-2009. However, applying the principle of not having actually performed the duties of the Senior Scientific Officer, we hold that such conferment of benefits shall be made on notional basis without any monetary liability. Above directions shall be carried out within two weeks from the date of production of the copies of this order.”